My Family’s Obon Journey and Reflections / 家族とお盆

(日本語は後半にあります)

【English】

Hello, Summer Vibes Community! As a Japanese person, I’m excited to share a piece of my culture and personal experiences with you all🥰

Japan has a traditional custom called Obon, a summer ritual where families welcome and honor the spirits of their ancestors at home.

On August 13, we light a welcome fire (a small fire, often in a lantern or outside the house) to guide the spirits back home. Offerings such as fruit, rice, or rice dumplings are placed on the family’s Buddhist altar (a small household shrine) to greet the spirits.

During Obon, families and relatives gather to visit graves and pay respects to their ancestors. I, too, return to my hometown almost every year during this time.

In many communities, Bon Odori, or Bon dances, are held at shrines or public spaces. These dances are performed to comfort and entertain the spirits.

On August 15 or 16, we light a send-off fire to guide the spirits back to the afterlife. These are the main features of Japan’s Obon.

This year, I spent Obon at my parents' home again. Inspired by some insights I gained during this time, I’m writing this article.

"My parents' home" refers to "my father’s parent' home". The Buddhist altar and graves belong to my father’s parents and grandparents. Therefore, my father takes on most of the responsibilities related to the altar and graves.

When I return home with my husband and sons to pray at the altar or visit the graves, it feels like we’re not only honoring our ancestors but also, indirectly, showing respect for my father.

Since realizing this, I’ve made it a point to bring extra souvenirs when I return home and pile them generously in front of the altar. This time, too, I brought souvenirs, including those for my siblings and relatives, and placed them all on the altar first. A quirky “souvenir tower” formed in front of the altar, but my father seemed pleased.

Let me share a bit about how the altar is decorated during Obon.

During Obon, many families set up a special platform called a Bon shelf or spirit shelf in front of the Buddhist altar. This shelf serves as a temporary altar to welcome ancestral spirits, adorned with offerings and decorations to show respect.

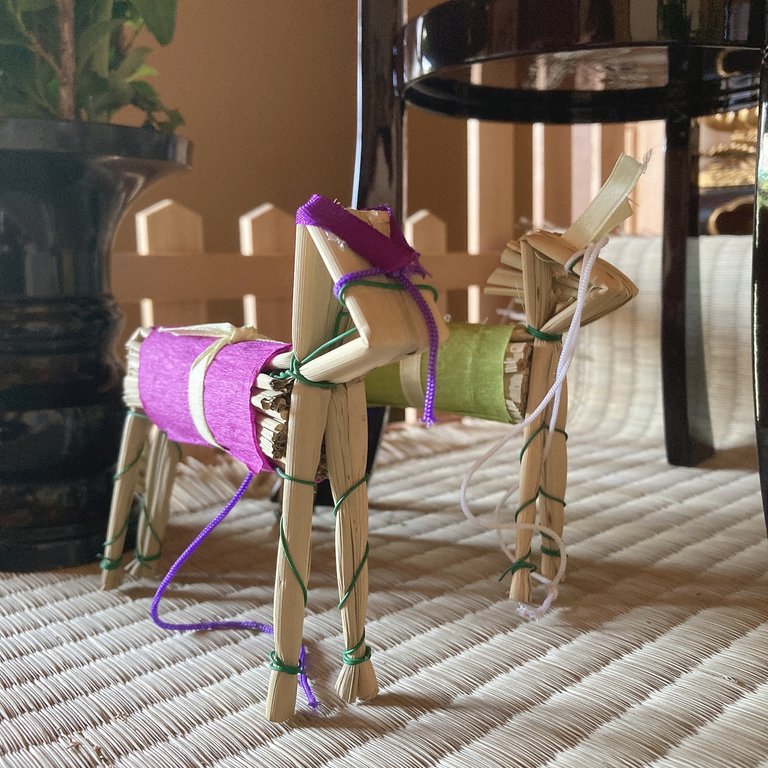

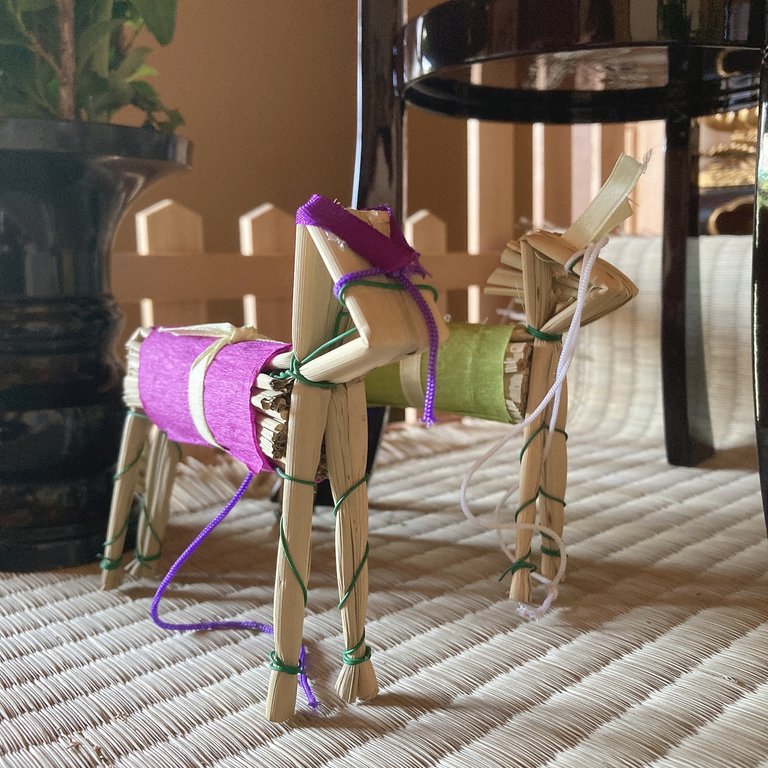

When my grandparents passed away, the Obon decorations were elaborate, with lanterns and other items prepared with great care. This year, however, the setup was more simplified, with a minimal arrangement. Until a couple of years ago, my mother used to make spirit horses using eggplants and cucumbers (I found a photo of the spirit horses she made in 2018, which I’ve included here). Since last year, though, we’ve been using a pre-made Obon kit, with artificial hōzuki (Chinese lantern plants) and chestnuts.

I think that’s perfectly fine. I believe it’s enough to honor the spirits with heartfelt offerings without placing too much burden on the living.

By the way, spirit horses are symbolic vehicles for the ancestral spirits to travel between this world and the afterlife. Cucumbers represent horses, symbolizing a swift journey to this world, while eggplants represent cows, symbolizing a slow return to the afterlife. I remember hearing about the meaning of the cows and horses as a child, and I find it quite charming.

The Bon shelf was adorned with fruits and rakugan, traditional Japanese sugar candies, as offerings.

Since we arrived at my parents' home in the evening, we visited the grave the next morning. My father told me that flowers wilt quickly in the summer heat, so we didn’t need to bring any. Instead, we just replaced the water at the vases.

After lighting incense, my sons and I read the Buddhist posthumous names (special names given to the deceased in Buddhist tradition) carved on the gravestone. Only four of my ancestors—my grandparents and great-grandparents—had their age at death (called kyōnen in Japanese, meaning the age at which someone passed away) inscribed below their posthumous names. Earlier ancestors didn’t have this, perhaps because their exact ages weren’t known or it wasn’t customary to include them.

Remarkably, all four of them lived past 90, with my grandfather being the longest-lived at 97.

With such long-lived parents and grandparents, my father might have a genetic predisposition to live a long life too… And since I share half his genes, I might live into my 90s as well. This thought made me realize I haven’t even reached the halfway point of my life, which felt a bit daunting.

At the same time, it was encouraging to think that I still have plenty of time to do anything I want and that it’s never too late to start something new.

Reflecting on these experiences, I felt inspired to share this story with others who might connect with the traditions and emotions of Obon. This brings me to a special note of gratitude. I’d like to thank @enraizar for encouraging me to write this article. Thank you for inviting me to this community, for always reading my posts, and for your kind comments. I’m truly grateful😊

※All photos were taken by me

【Japanese】

日本には「お盆」と呼ばれる習慣があります。ご先祖様を自宅に迎えて供養する、夏の風習です。

8月13日に「迎え火」を焚き、霊が家に戻る道を照らす。

家の仏壇にお供え物(果物、米、団子など)を置き、霊を迎える。

「お盆」期間中は家族や親戚が集まり、墓参りをして先祖を敬う(私もほぼ毎年、お盆時期は実家に帰省します)。

地域の神社や広場では「盆踊り」が行われることが多く、これは霊を慰め、楽しませるための踊りです。

そして8月15日または16日に「送り火」を焚き、霊をあの世へ送り返す。

これらが日本のお盆の主な特徴です。

さて、そんな「お盆」を今年も実家で過ごしました。今回、「お盆」を通じて得たいくつかの気づきを元に、この記事を書いています。

「私の実家」というのは、「父の実家」になりますーー つまり、仏壇やお墓に眠っているのは、父の両親や祖父母、ということです。だからお墓や仏壇周りの仕事は、主に父が担当しています。

私が夫や息子達を連れて帰省し、皆で仏壇に手を合わせたりお墓参りをしたりすることは、ご先祖さまだけでなく(間接的にではありますが)父を尊重することになるようです。

そのことに気づいてからは、帰省時にはお土産を多めに買い、仏壇の前にモリモリに積むようにしています。今回も同様にお土産を買い、兄弟や他の親戚に渡すお土産も一旦全て仏壇へ。仏前には奇妙なお土産タワーが出来上がりましたが、父は満足そうでした。

少し、お盆時期の仏壇の飾りについてお話しさせてください。

お盆の時期には、「盆棚」や「精霊棚」と呼ばれる特別な台を用意し、仏壇の前に飾ることが多いです。盆棚とは先祖の霊を迎えるための祭壇で、供え物や飾り物を置いて敬意を表します。

祖父母が亡くなった直後のお盆では、提灯なども用意し、飾りつけには気合が入っていました。しかし、今年は簡略版というか、シンプルな飾り付けでした。

一昨年くらいまでは、母がナスときゅうりを使って「精霊馬」を作っていました(2018年に母が作った精霊馬の写真が残っていたので、貼っておきます)。去年からは既製品の一式で済ませているそうで、鬼灯や栗も作り物でしたが、私はそれで充分だと思います。

生きている者の負担にならない程度に、気持ちを込めて供養すれば良いと考えています。

ちなみに精霊馬とは、先祖の霊がこの世とあの世を行き来するための乗り物で、きゅうりで馬を、茄子で牛を象徴します。行きは馬に乗って早くこちらに来て欲しい、帰りは牛に乗ってゆっくり帰って欲しい、という意味があるそうです。牛と馬に込められた意味については子どものころに聞いた記憶がありますが、素敵だなと思います。

盆棚には、果物や落雁(らくがん)といったお菓子が供えられていました。

帰省当日は夕方になってしまったため、お墓参りには翌朝行きました。父曰く、真夏はすぐに萎れてしまうので花は供えなくて良いとのことで、花瓶の水だけ変えました。

お線香をあげたあと、息子たちと一緒に墓石の横に刻まれた故人の戒名を読んでみました。私の祖父母、曾祖父母の4人のみ戒名の下に享年が彫られており、それ以前は正確に分からなかったのか、彫る習慣がなかったのか、記載はありませんでした。

しかしその4人は皆、見事に90歳を超えてから亡くなっていました。祖父が最も長寿で、97歳でした。

長寿の両親、祖父母を持った父は、遺伝子的に長生きする可能性がありますね… また、その血を半分ひいている私も、90代まで生きることになるかもしれません。そう考えると、まだまだ人生折り返し地点にすらきていないことになり、少々気が遠くなりました。

と同時に、まだまだ何をするにも充分な時間がある、何を始めるにしても遅くはない、と少し励まされるような気持ちにもなったのでした。

以上が、今年の私のお盆です。

最後に、この記事を書くきっかけをくださった@enraizarさんにお礼を言いたいと思います。私をこのコミュニティに招待してくれてありがとう。いつも私の投稿を読んでくれてありがとう。親切なコメントにも、とても感謝しています。

Posted Using INLEO

Obon has a really deep meaning and I only knew a portion of it til I read your post. It’s such a detailed explanation including the cucumbers and eggplants.

Customs such as welcoming and sending off fires, and spirit horses have existed in my parents' home since I was a child. However, I too only knew fragments of their meaning, so I researched them again when writing this article! 😉

Hello @go-kyo, it was a great joy for me to read this post. I live in Spain, but I am coming from a different country. We don't have such a meaningful celebration as you explained here, so thank you very much for introducing it to us, who may not have heard about it before. I see it as a very respectful and heartfelt event, honouring your ancestors. Thank you very much, and welcome to the Summer Vibes community! 😇🙏

Hello, @mipiano !! I'm grateful for the opportunity to join this wonderful community😍

I wondered if other countries had similar customs, so I did some research and found that Mexico's “Day of the Dead” may be similar🤔

When I was a child, I used to enjoy watching cucumber horses and eggplant cows or I would gaze blankly at the bonfires. In recent years, I have finally come to realize that this is an event to remember our ancestors!

Thank you for such an interesting insight into part of the Japanese culture.

Just curious, does your married status makes any difference to your participation in the ceremony at your parents home? In our Chinese culture in Hong Kong, now I'm married, strictly speaking I cannot make incense offering in my ancestral temple because I am not part of the family anymore. Whereas my husband can, maybe as a guest? (I never found out the official reason). Luckily customs are more relaxed nowadays with the passing of more traditional elderlies.

Your reply is upvoted by @topcomment; a manual curation service that rewards meaningful and engaging comments.

More Info - Support us! - Reports - Discord Channel

Thank you for reading my article🙂🙂

Your question is very valid! As far as I know, in Japan, it is not that you cannot visit your parents' grave after getting married, but the idea that you should prioritize your husband's ancestors' graves may still be strong. If the two families' graves are not too far apart, I think many people visit both graves and offer incense.

Note: In Japan, married couples take the same surname, and since I changed my surname to my husband's, strictly speaking, I am now a member of my husband's family.

As for me, my husband's family has already divorced, so there is no tradition of gathering during Obon. He is from Kyushu, and since it's not possible to return by plane, he hasn't been back for years. Additionally, the grave is located deep in the mountains...

However, it is also important to honor my husband's ancestors, so we have discussed visiting Kyushu this year to pay our respects at the grave!

Hello @go-kyo, first, I want to thank you for the mention and tell you how fortunate I was to have met you. This time, the gratitude is mutual. Despite your lack of time, you've always made time to respond to me, and now I sincerely thank you for this post.

As you can imagine, I knew nothing about the Obon tradition. I enjoyed this post from the first letter to the last.

I think we in the West are losing that respect and gratitude for our ancestors that you describe. It's a shame.

I also wanted to tell you that you're right, it's never too late to start something new.

I'm still on vacation, but I've been happy to break my decision to stay away from social media for a few days.

Thank you so much again for sharing a part of Japanese culture.

A big hello. 🤗

Your reply is upvoted by @topcomment; a manual curation service that rewards meaningful and engaging comments.

More Info - Support us! - Reports - Discord Channel

While looking into foreign customs to explain Japan's "Obon" in a simple way, I found that Mexico's "Day of the Dead" might be somewhat similar.

I think Obon is a wonderful tradition in concept, but for some people, actually going back to their hometowns and gathering with relatives can bring various stresses. Quite a few people feel reluctant about returning home in the summer.

I hope we can cherish not only our ancestors but also the living family and relatives🥰

Thanks for reading, no need to reply—have a safe and enjoyable trip!✈️🛫